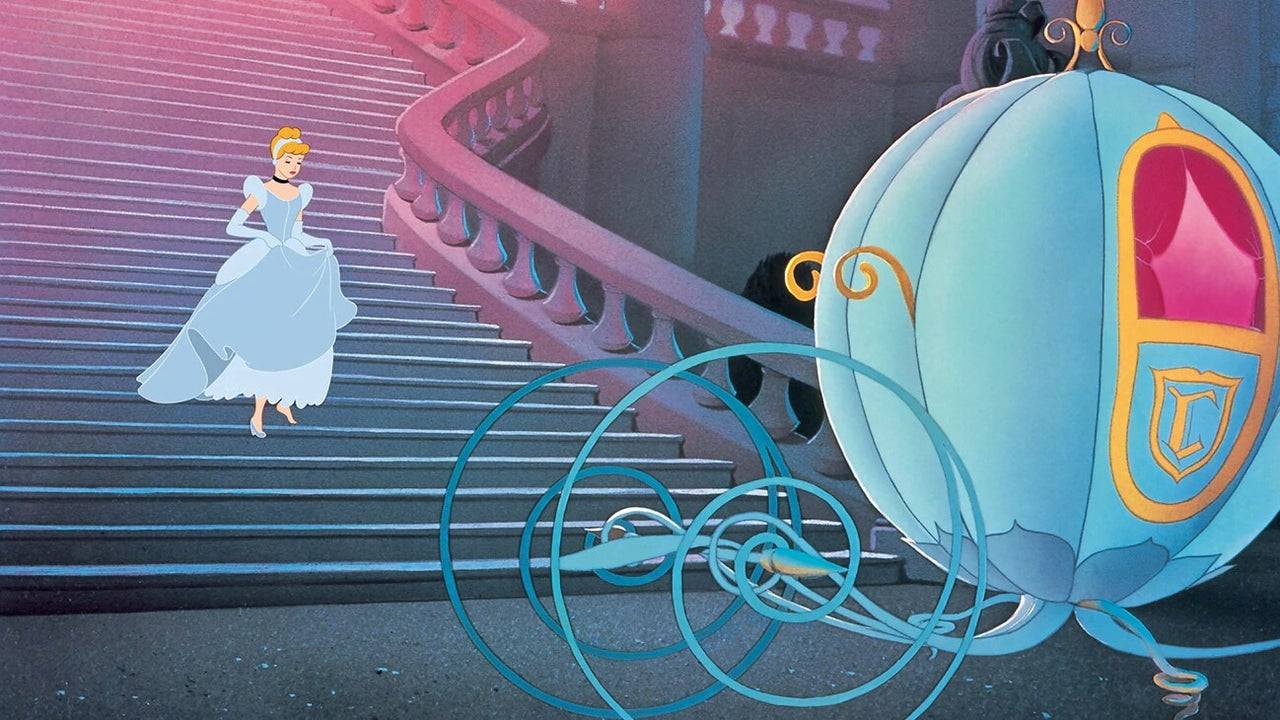

Just as Cinderella's dream was set to end at midnight, The Walt Disney Company faced its own critical moment in 1947, grappling with a debt of roughly $4 million due to the financial struggles of films like Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Bambi, exacerbated by World War II and other factors. However, the enchanting tale of Cinderella and her iconic glass slippers played a pivotal role in rescuing Disney from an early end to its animation legacy.

As Cinderella celebrates its 75th anniversary of its wide release on March 4, we engaged with several Disney insiders who continue to draw inspiration from this timeless rags-to-riches story. This narrative not only echoes Walt Disney's personal journey but also rekindled hope within the company and a post-war world yearning for something to believe in.

The Right Film at the Right Time --------------------------------To understand the significance of Cinderella, we must look back to Disney's transformative moment in 1937 with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. This film's unprecedented success, which held the title of the highest-grossing film until Gone with the Wind surpassed it, enabled Disney to establish its studio in Burbank, its current headquarters, and set the stage for future animated feature films.

Following Snow White, Disney's 1940 release Pinocchio, despite its $2.6 million budget and critical acclaim, including Academy Awards for Best Original Score and Best Original Song, resulted in a $1 million loss. Similarly, Fantasia and Bambi underperformed, contributing to mounting debts. The onset of World War II played a significant role, as noted by Eric Goldberg, co-director of Pocahontas and lead animator on Aladdin's Genie: "Disney's European markets dried up during the war, and the films weren’t being shown there, so releases like Pinocchio and Bambi did not do well. The studio was then tasked by the U.S. government to produce training and propaganda films, shifting focus to Package Films like Make Mine Music, Fun and Fancy Free, and Melody Time, which, while cost-effective, lacked a cohesive narrative."

Package Films were compilations of short cartoons, a format Disney utilized between the releases of Bambi in 1942 and Cinderella in 1950, including Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros under the U.S.'s Good Neighbor Policy to counter Nazism in South America. These films managed to recoup their costs, with Fun and Fancy Free reducing the studio's debt from $4.2 million to $3 million by 1947, yet they hindered the production of true feature-length stories.

Walt Disney's determination to return to feature animation was evident in his 1956 statement, as quoted in The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney by Michael Barrier: "I wanted to get back into the feature field. But it was a matter of investment and time. Now, to take and do a good cartoon feature takes a lot of time and a lot of money. But I wanted to get back. And my brother [Disney CEO Roy O. Disney] and I had quite a screamer… It was one of my big upsets… I said we’re going to either go forward, we’re going to get back in business, or I say let’s liquidate or let’s sell out."

Facing the possibility of selling his shares and leaving the company, Walt and Roy Disney decided to take a bold risk and invest in their first major animated feature since Bambi. The choice fell on Cinderella, which shared thematic similarities with the successful Snow White. Tori Cranner, Art Collections Manager at Walt Disney Animation Research Library, emphasized the film's timely message: "Walt was very good at reflecting the times, and I think he recognized what America needed after the war was hope and joy. And while Pinocchio is an incredibly beautiful and amazing movie in and of itself, it's not a joyful movie in the way Cinderella is. And I think the world needed the idea that we can come out from the ashes and have something beautiful happen. Cinderella was the right choice for that moment in time."

Cinderella and Disney’s Rags to Riches Tale

Walt Disney's fascination with Cinderella dates back to 1922, during his time at Laugh-O-Gram Studios, where he created a Cinderella short. This early work, adapted from Charles Perrault’s 1697 version of the tale, resonated with Walt due to its themes of good versus evil, true love, and dreams coming true, mirroring his own journey from humble beginnings to success through perseverance.

Walt's reflections on Cinderella highlight her proactive nature: "Snow White was a kind and simple little girl who believed in wishing and waiting for her Prince Charming to come along. On the other hand, Cinderella here was more practical. She believed in dreams all right, but she also believed in doing something about them. When Prince Charming didn’t happen to come along, she went right over to the palace and got him."

Cinderella's journey, marked by resilience against her Evil Stepmother and Stepsisters, mirrors Walt's own path of overcoming numerous challenges. Initially considered for a Silly Symphony short in 1933, the project evolved into a feature film by 1938, finally hitting the screens in 1950 after delays due to the war and other factors.

The success of Cinderella can be attributed to Disney's ability to enhance classic fairytales, as Eric Goldberg noted: "Disney was so good at taking these fairytales that had been around for many, many years and putting his own spin on it. This meant he brought his taste, entertainment sense, heart, and passion into it so people came to care about the characters and story unfolding even more than in the original stories themselves. These fairytales were also, excuse the pun, a little bit grim because they were often meant as cautionary tales for younger people. What Disney did, however, is he made these stories universally palatable and enjoyable for all audiences, which helped modernize them and let them stand the test of time."

Disney's additions, such as Cinderella's animal friends and the bumbling Fairy Godmother, added depth and relatability to the story. The iconic transformation scene, particularly the dress transformation, remains a highlight, with Tori Cranner praising its meticulous hand-drawn and painted sparkles: "First of all, you have to remember that every single one of those sparkles was hand-drawn on every frame and then hand-painted, which just blows my mind. But there's also a part of it that’s so subtle, as there is a perfect moment in the middle of that transformation where all of the stardust and the magic holds for just a fraction of a second before it all falls in and her dress changes. I really think that that's part of what makes that scene so magical. It's almost a second of holding your breath and then the release comes and you know that magic just happened."

The addition of the breaking glass slipper at the film's end underscores Cinderella's agency and strength, as highlighted by Eric Goldberg: "I think something that a lot of people overlook is that Cinderella is not a cipher. She’s not a bland female protagonist that you might see in some of the other films, but she has a personality and a strength within her. When the stepmother causes the glass slipper to break, Cinderella has the solution to it by presenting the other one she had been holding on to. It’s such a powerful moment and a clever story thing to show how strong and in control she actually is."

Cinderella premiered in Boston on February 15, 1950, and enjoyed a wide release on March 4, becoming an instant success with a box office performance that surpassed any Disney film since Snow White, earning $7 million on a $2.2 million budget. It received three Academy Award nominations and was lauded by critics, as Eric Goldberg recalls: "When Cinderella came out, all the critics went, ‘Oh, this is great! Walt Disney's back on track again!’ It was hugely successful for them because he was back doing narrative features like Snow White and people just loved it. I think the studio also got their mojo back, so to speak. They loved the Package Films and the work they did during the troubled times of the war, but this is what the studio was built for. Following Cinderella, Disney continued on to develop films like Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, 101 Dalmatians, Jungle Book, and so many more, and it was all thanks to Cinderella."

75 Years Later, Cinderella’s Magic Lives On

Seventy-five years later, Cinderella's influence remains profound within Disney and beyond. Her iconic castle graces Main Street, U.S.A. at Walt Disney World and Tokyo Disneyland, and her legacy inspires modern Disney films, such as the dress transformation scene in Frozen, as noted by Frozen 2 and Wish lead animator Becky Bresee: "When we were doing Elsa’s dress transformation moment in Frozen, which I animated along with effects artist Dan Lund, co-director Jennifer Lee wanted it to have a direct connection to Cinderella. Cinderella’s legacy can especially be seen in the sparkles and all the effects surrounding Elsa’s dress, and although she is a much different character, there are so many moments and things we bring forward to honor the impact of Cinderella and other movies that came before."

The contributions of the Nine Old Men and Mary Blair to Cinderella's distinctive style and character are also noteworthy. As we reflect on this classic tale, Eric Goldberg encapsulates its enduring message: "I think the big thing about Cinderella is hope. It gives people hope that things will work out when you have perseverance and when you are a strong person. I think that's its biggest message… is that hope can actually be realized and dreams can come true, no matter what time you are living in."